Alarm bells are ringing across the high-end sector. 2024 did not end as luxury brands had hoped, and the figures published by the sector’s main conglomerates painted a picture of slowdown and some signs of exhaustion during the last quarter of 2024. The weakening Asian market is one obvious cause, but consumers’ unusual reactions to sharp price rises has also been striking. Aspiration and distinction – which were part of luxury brands’ DNA until recently – are taking on new dimensions thanks to phenomena, such as ultra-fast fashion and “dupe” culture.

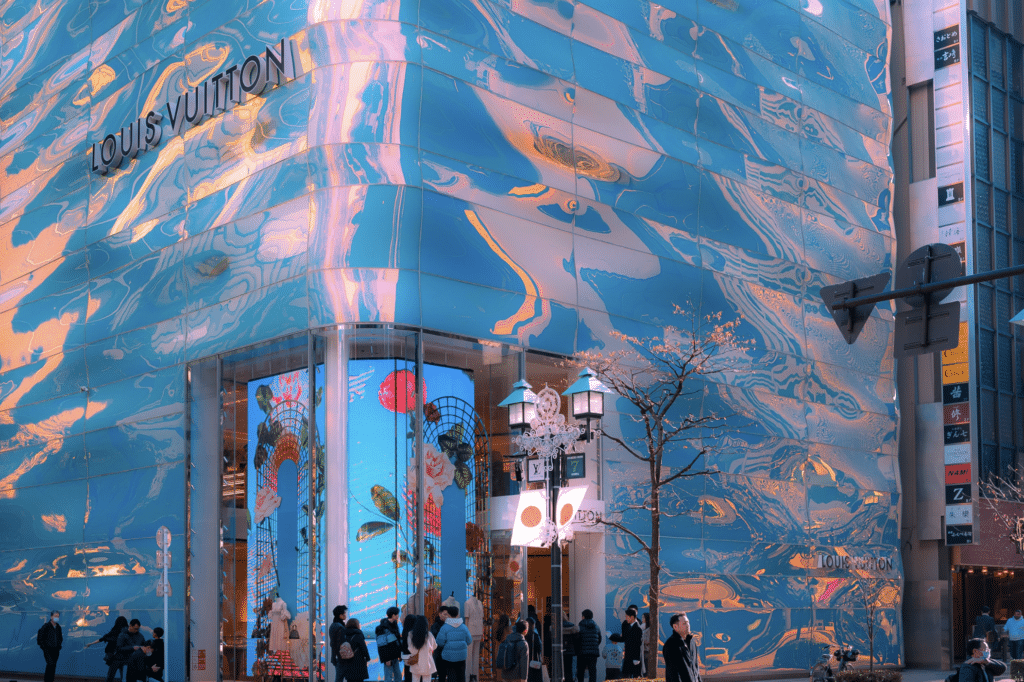

In a striking sign of decline, LVMH presented its results for Q3 in October, reporting its first decline in quarterly sales since the pandemic. The luxury goods titan – which owns upwards of 70 brands, including Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, Moёt & Chandon, Hennessy and Veuve Clicquot – revealed that sales fell by 4 percent compared the same quarter in 2023. Meanwhile, Gucci, Balenciaga, Saint Laurent, and Bottega Veneta owner, Kering, reported that Q3 revenue was down 15 percent as reported and down 16 percent on a comparable basis. The list of examples goes on, with other luxury brands publishing similarly disappointing revenue figures.

The results could be analyzed in light of the last year’s growing panorama of global instability. 2024 saw intense geopolitical turmoil, with multiple serious open conflicts, burgeoning technological rivalries, and more than 70 elections around the world, including a presidential election in the United States. This all brings with it a strong degree of economic uncertainty.

However, it is worth remembering that the luxury market has been very resilient in times of crisis. The sector’s post-COVID crash results were surprisingly good: digitalization accelerated, and the buoyant behavior of consumers with a desire to splurge – a phenomenon known as “revenge spending” – helped significantly. So, what might this change in consumption mean, and what lessons can we learn from it? There are several significant factors that may herald a transformation in the world of luxury, and companies’ strategies will have to change if they want to keep up.

Asian economies are getting weaker

One of the decisive factors in these results is the fading idea of China as a source of unstoppable growth. In recent years, breaking into the Chinese market was the main ambition for luxury goods brands, their natural place of expansion and growth. Between 2009 and 2019, for instance, LVMH’s brands as a whole went from having 470 outlets in Asia to 1,453 (excluding Japan). The same is true for Kering, which saw its retail outposts rise from 152 to 609.

Collections and marketing strategies have also shifted towards this market, specifically targeting a growing and thriving middle class on the Chinese mainland, which seemed to have no end in sight. However, the dragon economies are now showing signs of slowing, and in the luxury sector, the drop in sales is becoming quite pronounced.

In its Q3 report, LVMH cited a 16 percent drop in Asian sales (again, excluding Japan). The drop is especially pronounced in China, which previously accounted for 50 percent of the French group’s growth. Lack of consumer confidence and restrained spending on luxury goods may explain this new outlook. But if China is not what it used to be, where can luxury brands find new winning strategies?

Prices keep going up

The strategy of the luxury groups has been based in recent years on an extraordinary rise in prices. The escalation has been unstoppable, with Chanel bags reaching beyond €10,000, Hermès announcing that it would lift prices by between 8 and 9 percent across the globe, causing the price tag on Birkin bags to jump by more than $1,000, etc. All the while, some of these pieces have also doubled in value on the second-hand market. The price of watches is another clear example, with increases of more than 20 percent coming into fruition in certain cases.

It is natural for luxury brands to use price as a barrier to entry for mass consumption and as a way of preserving exclusivity. In theory, the boosts appeal to the ultra-rich or extremely wealthy, with the purpose of creating eternal aspiration – the Veblen effect, by which higher prices generate higher demand, has worked in this market.

The concept is named after Thornstein Veblen, economist and author of The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions. In chapter seven of this work, entitled “Dress as an Expression of the Pecuniary Culture,” Veblen explains that fashion and luxury are status indicators. If aspiration is not constructed, luxury becomes meaningless. However, there seem to be other reasons for this striking price increase. One widely reported reason is the higher cost of raw materials, but geopolitical uncertainty and runaway inflation in recent years have also contributed to the rise.

The cost of distinction

The entry of new players into the fashion world at the bottom of the pyramid has forced everyone to move up the ladder, and to find what sets them apart. Ultra-fast fashion has made mid-market brands (and even early purveyors of fast fashion) want to be perceived as more aspirational, and this movement in turn leads luxury brands to seek greater distance from new competitors.

Some also point to “dupe” culture as the culprit for this steady price progression. Copies of luxury products – or imitations with slight modifications – have flooded social media, especially TikTok, forcing brands to distance themselves further from this type of consumption. Authenticity comes at a price. The big question right now is how far this price escalation will go. Some people have asked whether the consumers targeted by these brands, no matter how great their fortune, also have reservations about spending for spending’s sake. In other words, do they really find value in the product?

Quiet luxury: a new approach

It seems that it is no longer enough to position oneself as a luxury brand – these companies also have to find a way to create and demonstrate value. Price increases need to be justified by two of the levers that have always been the essence of luxury: creativity and quality. Additionally, luxury is no longer synonymous with brands. The trend of quiet luxury (and more recently, quiet logos) shows a desire to distance oneself from flashy aggressiveness by avoiding or downplaying logos or characteristic details that make its brand obvious.

This means brands are only recognizable to those who have a more cultivated knowledge of luxury products. Silent luxury potentially broadens the market to clients who, beyond products themselves, are also interested in their own wellbeing and a more relaxed way of life.

Teresa Sádaba is the Dean at ISEM Fashion Business School at Universidad de Navarra.